In case you haven’t noticed, space is big.

And I mean big. 93 billion light years in diameter, according to NASA, or around 1 trillion trillion kilometers if you prefer. Of course, we are just talking about the size of the observable universe, a sphere centered on our planet (technically on you, the Observer) which represents every light signal, real or imaginary, which has had time to reach you since the beginning of cosmological expansion.

Space almost certainly extends beyond this distance, perhaps even infinitely, but any regions outside of this sphere are purely hypothetical since such regions would be causally disconnected from you.

Regardless of what might lie beyond, our visible part of the universe is big enough to hold our interest and offer some pretty interesting photo ops.

But how far can we see into space? What is the most distant object that can be photographed?

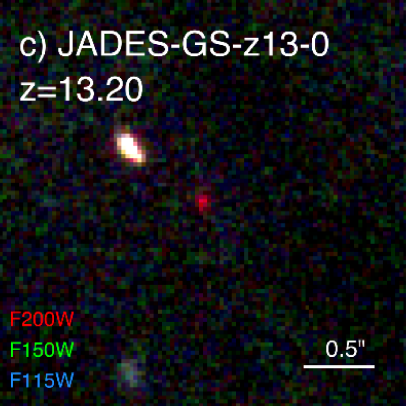

The answer is changing as I type this, as the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) unlocks a new realm of possibility in astro-imaging.In September 2022, the JWST discovered a blob of light since named JADES-GS-z13-0. According to redshift measurements, this baby galaxy lies at some 33.6 billion light years from Earth, having formed in the earliest eons after the Big Bang. To date, this is the most distant object on record.

You would be right to wonder how there could be anything beyond 13.8 billion light years, since the event we call the Big Bang happened around 13.8 billion years ago and light travels at a rate of 1 light year per year.

The answer is a bit complicated but has to do with the expansion of space, which causes more distant parts of space to recede from us more rapidly until it pushes them beyond our particle horizon and outside of the observable universe.

How is it possible to capture images of something so far? What sort of reach should you expect from your backyard telescope? And is it possible to photograph galaxies yourself? Let’s look at each of these questions in turn.

How Can We Take Pictures of Something So Far Away?

Capturing a photographic image requires only one thing: light to reach your camera sensor. For a distant galaxy, we are talking about the barest trickle of photons.

Long exposures are used to capture more detail than would ever be possible with the eye alone. Additionally, every optical system, be it your eye, camera lens, or telescope, has a limiting magnitude which sets a boundary on the faintest object it can detect.

Larger systems like professional telescopes have very high limiting magnitudes as well as much higher resolution than backyard telescopes. Detecting fainter signals means seeing deeper into space.

Sometimes, a big telescope isn’t enough to get the job done. Earth’s atmosphere can act like a dirty window to view through, which is why we have space telescopes like the Hubble. This avoids not only urban light pollution and atmospheric turbulence, but also the natural “airglow” present in even the darkest Earthly skies.

For the most distant galaxies, even that may not be enough. This is where an instrument like the JWST comes into play.

Aside from having incredibly high limiting magnitude due to its sheer size, it is also designed to operate at infrared wavelengths, allowing it to see objects so distant that all their emitted light has been stretched out of the range of visibility.

How Far Can Backyard Telescopes See?

This figure will depend on several factors: the size and quality of your telescope, the quality of your skies, your visual acuity, and your experience level.

An 8-inch Dobsonian or similar instrument will easily capture dozens of galaxies in the 50 million light-year range from suburban skies, and can reach much deeper under dark rural skies.

Larger telescopes will have even greater reach, provided they are kept clean and well-collimated. My personal record is around 300 million light years using my 12-inch reflector to view Stephan’s Quintet in Pegasus.

In fact, a telescope isn’t even required to see deep into space. The Andromeda Galaxy (M31) can be spotted with the naked eye, at around 2.5 million light years. That seems like an impossible feat until you consider that M31 is around 150 thousand light years in diameter and shines with the combined light of a trillion stars!

A simple pair of birdwatching binoculars can improve matters dramatically, allowing you to catch objects like Bode’s Galaxy in Ursa Major at 12 million light years.

How to View Distant Galaxies

Even a top-quality telescope and pristine skies are not enough to guarantee maximum deep-sky penetration. This is where experience comes into play: knowing not just where to look but how to look. Here are five tips for viewing these majestic faint fuzzies:

- Allow your eyes to become dark-adapted.

- Get seated at a comfortable level so you aren’t stretching or crouching to view.

- Use star charts and a red flashlight to identify objects of interest. Knowing their apparent size and magnitude will also help you spot them.

- Use averted vision instead of staring directly at the object.

- Have patience. Rather than straining to see the galaxy, relax your eyes and let the image come to you.

Photographing Galaxies

There is no single way to shoot galaxies. A DSLR with a wide-angle lens on a tripod is enough to capture M31, but most other galaxies have a much smaller apparent size and will not be so obvious in wide-angle photos.

A telephoto lens and a star tracker mount like the Sky-Watcher Star Adventurer will start to open up some other bright galaxies like M33 and M101.

Shooting galaxies through a telescope is the recommended method, but generally requires a robust tracking mount capable of supporting longer exposures.

Many beginning astro-imagers start with a small refractor on an equatorial mount such as the Sky-Watcher EQM-35 or the AVX from Celestron. But there is no harm in playing around with equipment you have on hand. If all you have is a cell phone and eyepiece adapter, here are a few things to try.

Tips for Shooting Deep-Sky Images with a Cell Phone

- Use an adapter to hold the phone in place over your low-powered eyepiece.

- Shoot in the highest-quality format available.

- Experiment with ISO and shutter speed to get the most detail without blurring.

- Use a timed shutter release to avoid vibrations from your fingers.

- Take multiple shots and try stacking them with software such as Deep Sky Stacker.

I have even more tips available on my 9 tips for getting started with smartphone astrophotography page.